Melissa Wood

woodm2@si.edu

(202) 297-6161

Fleur Paysour

paysourf@si.edu

(202) 294-0666

New Objects Are Available Online in Celebration of the 250th Anniversary of the Publication of Wheatley Peters’s Poems, Including the Only Copy of the Poet’s Long-Lost “Ocean” Poem in Her Handwriting

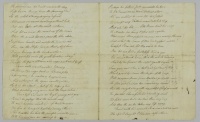

(Black PR Wire) The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) has acquired the largest private collection of items to bring new context and perspective to the life and literary impact of poet Phillis Wheatley Peters (c.1753–1784), including one of the few manuscripts written in the poet’s hand. Born in West Africa and captured by slave traders as a child, Wheatley Peters became the first African American to publish a book of poetry with the 1773 release of her “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” in London. A rare and exciting highlight of this acquisition is a four-page manuscript of a poem, “Ocean,” written in ink by Wheatley Peters's own hand, the only copy that exists today and previously unpublished before 1998. The poem was likely composed on her return voyage to America from England in September 1773.

Of the 30 objects in this collection, six were published during her lifespan. Selected items from the collection can be viewed online through the Searchable Museum website. Plans to display these new acquisitions at a later date are in the works. The museum currently recognizes Wheatley Peters in the Paradox of Liberty display in the Slavery and Freedom exhibition with a statue and a copy of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.

“Phillis Wheatley Peters’s poetry brought her renown in abolitionist circles and presented as proof of the humanity of those of African descent and the inhumanity of slavery,” said Kevin Young, the Andrew W. Mellon Director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Scholars continue to parse through her work to determine when and where she posed resistance to slavery; her poem ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’ is considered to be a chastisement of slavery to the millions of white Americans undergoing the religious revival movement known as ‘The Great Awakening.’ This must have pricked Thomas Jefferson’s conscience, for his 1785 publication of Notes on the State of Virginia dismissed Wheatley Peters’s talent as coming from religion and religious training rather than intellect.”

Some additional highlights of the collection include:

- Autograph manuscript of 70-line dramatic poem, “Ocean,” by Wheatley, ca. September 1773, four pages.

- An issue of The Arminian Magazine, August 1789, features the 20-line poem “On the Death of a Child, Five Years of Age” and attributes it to “Phillis Wheatly, a negro.”

- A hardcover edition of the book Pearls From the American Female Poets by Caroline May, 1869. The entry for Wheatley Peters spans pages 39 to 41 and includes a biographical note and two poems: “On the Death of a Young Gentleman of Great Promise” and “Sleep.”

- A hardcover edition of the book The Poems of Phillis Wheatley, 1909. The red cloth cover features Wheatley Peters in profile and holding a quill to paper in her right hand.

- A hardcover edition of the book Phillis Wheatley (Phillis Peters): A Critical Attempt and a Bibliography of Her Writings by Charles Frederick Heartman, 1915. Translated into English from the original German.

- Booklet published by the Phillis Wheatley Club of Waycross, Georgia, in 1930. Contains a biography of the poet and correspondence between Wheatley Peters and George Washington, including a poem she sent him, “His Excellency General Washington.”

The publication of her poems by the AME Church and a biography by the Phillis Wheatley Club in the early 20th century are the only works in the collection published by Black printers. The biography published by the Phillis Wheatley Club takes on a higher level of importance because it documents the educational work of Black clubwomen and the role Black women played as historians of Black life and culture.

“This collection, ranging from the late 18th century to the early 20th century, provides a glimpse of Phillis Wheatley Peters the poet and Wheatley Peters the icon, as well as Wheatley Peters the woman,” said Angela Tate, curator of women’s history at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “This part of Wheatley Peters life has been long removed from popular culture and remembrance. A 1783 poem in this collection is of extreme interest because it is published under her married name of Phillis Peters, and furthermore, it is important to note that she is not presented as Mrs. John Peters.”

About Phillis Wheatley Peters

Wheatley Peters spent most of her life enslaved and in service to John and Susanna Wheatley of Boston. She was named Phillis after the slave ship on which she was transported to the Americas. Her surname of Peters is that of the man she married in 1778, John Peters, a free man of color. Wheatley Peters’ owners taught her to read and write, and by age 14, she had begun to write poetry that would soon be published and circulated among the elites of late 18th-century America and Great Britain.

Her first and only volume of poetry, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” (1772), was published in London with the assistance of wealthy abolitionists. The Wheatleys manumitted Wheatley Peters in 1773 under pressure from critics who saw the hypocrisy in praising her talent while keeping her enslaved. They died within a few years of that decision and Wheatley Peters soon met and married grocer John Peters. Her life afterwards was indicative of the troubled freedom of African Americans of that period, who were emancipated but not fully integrated into the promise of American citizenship. Wheatley Peters was also affected by the loss of all three of her children—the birth of the last of whom caused her premature death at age 31 in 1784.

Despite being feted at as a prodigy while enslaved, the emancipated Wheatley Peters struggled to find the support necessary for producing a second volume of poetry, and her husband’s financial struggles forced her to find work as a scullery maid—the lowest position of domestic help.

Posthumous publications of Wheatley Peters’s poetry in various anthologies and periodicals solidified her image as a child poet for the benefit of abolitionist activism and African American cultural pride in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the 21st century, the accumulation of this collection is a restoration of Wheatley Peters the woman and the influence of her poetry and activism today.

About the National Museum of African American History and Culture

Since opening Sept. 24, 2016, the National Museum of African American History and Culture has welcomed more than 9.5 million in-person visitors and millions more through its digital presence. Occupying a prominent location next to the Washington Monument on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the nearly 400,000-square-foot museum is the nation’s largest and most comprehensive cultural destination devoted exclusively to exploring, documenting and showcasing the African American story and its impact on American and world history. For more information about the museum, visit nmaahc.si.edu, follow @NMAAHC on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, or call Smithsonian information at (202) 633-1000.

# # #

Source: National Museum of African American History and Culture